This paper is a retrospective and informative commentary on the first sentence of our Principles of Structure and Government: “The People of Praise is structured according to branches and program offices for its life and work respectively.” To integrate our life (being) and work (doing) we used what is called a “matrix” form of organization. The paper explains the purpose of this organizational structure, the nuts and bolts of this structure and the attitudes of mind and heart that are needed to make it work.

OUR PRINCIPLES OF STRUCTURE AND GOVERNMENT INTEGRATING LIFE AND WORK

The purpose of this paper is to present some of the principles we have used to structure the community. From the beginning of the community we have wanted to maintain the distinction between doing and being: being one with Christ and in Him with God our Father and doing what our Father wants us to do in some integrated way. In our Principles of Structure and Government we delineated a way to organize the community that allowed us to integrate our life (being) and our work (doing).

Life and work are integrated in the People of Praise using what we call a matrix form of organization. This form of organization was first developed and documented in the United States aerospace industry and was used extensively by NASA in the 1960s to manage its space flight projects. In the People of Praise, the two key components of this management system are the branches and the program offices. Thus in the opening paragraph of our Principles of Structure and Government one finds, “The People of Praise is structured according to branches and program offices for its life and work, respectively.”

This paper is divided into three sections. The first is a discussion of why we chose to organize our life this way. The second is a description of the actual matrix structure of the People of Praise. The third section is a discussion of what is needed to make the matrix work well.

For some people, this material might be a review, but it can be more than a review. It can be a help to what is going on in the branches. God seems to be stirring the hearts of people in various branches to do more things for him. So much so that it seems like a wave which is a visible phenomenon. This wave needs to be guided by the principles we’ve established about integrating being a community and doing particular works as a community. We want to help branches who are undertaking various projects in response to this stirring so that they can run their affairs in a way that doesn’t endanger their “being” community but does enable the people who want to do more. It is important to take into account our principles when branch projects are large enough and to run them according to these principles.

We hope the following exposition of our principles has the collateral benefit of educating new program coordinators, division coordinators, principal branch coordinators and area coordinators. Sometimes people take office not knowing or understanding the principles that govern our integrated life.

Why the Matrix

Purpose matters. A lot. One time a member of a branch in the States was visiting Trinidad and his host was driving him from one point on the island to another. It was clear that the road they were driving on had at one time been a magnificent, state-of-the-art highway, but that was no longer the case. The visitor asked what had happened. His host explained that German technicians had been hired to come to Trinidad to build highways and share their highway-building expertise with the Trinidadians, one Trinidadian shadowing each German. They had worked together for five years building an interstate for the island. After it was finished the Germans left and the well-trained crew of Trinidadians took over. However, instead of hiring workers with the needed expertise, they hired family members—their uncles and brothers and cousins, despite their lack of training. Gradually the roads deteriorated. Their highest priority wasn’t state-of-the-art roads. Their purpose was different. Their highest priority was taking care of family.

There are many different purposes for associating. Often people group together to share certain activities—running a prayer meeting, playing a sport, educating children, serving the homeless, etc. Sometimes they group together to share certain material things—a group of people who live in a given geographical region incorporate so as to share roads and sewers and so on. Sometimes they group together to share and promulgate a certain point of view, such as the alleged dangers of global warming or creationism.

Often, as these examples illustrate, organizations exist for some purpose other than their own relationships. Their reason for being a group lies elsewhere—they exist to do something, to accomplish something, for example, running a soup kitchen. Such relationships are often called functional. In other words, people relate to one another primarily to accomplish a work. Their relationships are not their primary purpose. Of course, the people involved do some interpersonal sharing and participate in common social events such as a staff picnic, which makes their association more enjoyable.

Here’s a true story of how General Motors handled these issues. The company did not want its top executives to form close relationships with their clients because if they did so, they would begin to make decisions for the good of their friends rather than for the good of the company. For example, an executive who had been in a locale long enough, might decide to do something because he owed a friend a favor. And to make sure this didn’t happen, the company relocated its executives every three years, disregarding the negative effects on family and friends. For the sake of profit, it was a matter of policy.

The People of Praise, on the other hand, exists for a different kind of purpose. For God “has made known to us in all wisdom and insight the mystery of his will, according to his purpose which he set forth in Christ, as a plan for the fulness of time, to unite all things in him, things in heaven and things on earth” (Eph. 1:9–10). God’s purpose is to create a people who are united to him—a unity of God and mankind, one Body. Our purpose as a community is drawn from his purpose—to build a people, a kinship group with God as our Father. Our plan is the same as God’s plan—to work to form a people united in Christ. Our focus is a Body of people and their gathering together under the Lordship of Jesus.

Our leaders then, have to do three things. First, they need to draw people to Jesus. Community is life in Christ. They must help each person grow up in every way into Christ, “until we all attain to the unity of the faith and of the knowledge of the Son of God, to mature manhood, to the measure of the stature of the fulness of Christ” (Eph. 4:13). Second, they need to draw people together and help them relate to each other under the Lordship of Jesus. A leader helps his brothers and sisters to know and love one another. This is, obviously, a process, a process that must constantly be attended to by pastoring—the process of people coming together in an ongoing way around Jesus. And finally, a leader has to provide whatever organization is needed for his brothers and sisters to come to union with God and each other. He must get his brothers and sisters all the help they need to live a full Christian life together.

Some might think, rightly so, that it is really hard to help someone become holy and to help a group of people become a holy people. So they settle for building an institution. For example, they run a routine, cookie-cutter area meeting rather than using an area meeting to build community among these particular people in these particular circumstances. Or they settle for building a functional organization or running a program. Relatively speaking, it’s not so hard to organize a group of people around a school or around door-knocking or around building homes for the poor. Functional organizations are easier to lead. They seem to have a life of their own, following their standard operating procedures. However, a group of people centered around a function—even a Christian function like evangelizing or serving the poor—is not what we call a community. Such an organization would not, for example, think it is responsible for its members in their old age or for helping to educate its members’ children.

God has brought us together not just to share certain activities or some material goods or certain points of view. He has brought us together to share our whole selves, which of course includes what we do, what we own and what we think, but it is more than that. We are a collection of disciples who in some measure leave fathers, mothers, brothers or sisters, children, lands and houses for the sake of the Gospel. The result of our being together, united in Christ, is mutual knowing and mutual love and therefore the acceptance of mutual responsibility one for the other.

Purpose matters and our purpose is “to be” not “to do.”1 That being said, it is also true that being together leads to activities that take care of people’s needs (putting a new roof on someone’s house) and that build up branch and/or area life (putting on a wedding reception). In fact, the more things a local community is jointly responsible for, the more there is for all to do. For example, if community members in a neighborhood jointly own a snow blower, then someone has to be responsible for keeping the gas can full, for its maintenance, for its scheduling, for settling disputes, etc. Such purposeful activities lead to a stronger sense of involvement on the part of community members.

We want to be the type of community where a member’s life-needs are met. Part of loving one another is taking care of one another’s needs. In fact, the more we have real economic, religious, political, recreational, educational, social, cultural, legal and charitable functions that serve the lives of our members, the stronger we are as a community and the more closely we are held together by God. The more we go to one another and/or to the local community as a whole for getting a job, for child rearing advice, for service when sick, for loans, for mutual aid, for help in decision making, for education, for spiritual direction, for companionship in old age, to settle a dispute, to have fun, to do something creative, to find a spouse, to praise and worship our Lord, the stronger a community we will become. Of course, it goes without saying that we want to do these things in Christ, as Christ—the way our Father teaches us to do them.

Activities can lead to more participation in our shared life. The right kind of activities build up the community and result in its having real functional significance in the lives of its members. And when a group has real functional significance in the lives of its members and real roles such as mother, father, man, woman, son, daughter, etc., that group will matter a lot to its members. Nonetheless, too much doing can be our undoing. Take for example a family. The father works to support the life—the being—of the family. But then, he thinks, “I could make more money to help my family” and he begins to work more. He comes home later and later. He buys a bike for his son, but doesn’t have time to teach him to ride it. Eventually, he’s working so late that his kids are in bed before he gets home. His activity, which was in the beginning for the sake of the family, becomes destructive of family life. So too in community life. We can become better and better at doing things and worse and worse at being together. However, that being said, it is possible for a community whose purpose is to be a people, united to God and one another in Christ to have real functional significance in the lives of its members.

Besides activities and projects that take care of one another’s needs and that build up our common life, there are also activities which are, from our point of view, not necessary to being a community. For example, publishing a magazine, or serving the poor in some way or sponsoring an evangelistic program are all projects that, while they may be important and may be what God wants us to do, are nonetheless not integral to being a community. It is important to keep this distinction in mind.

In the late 70s, we felt God was calling us to do more. We had been focused on our relationships and on being a community, but we were reaching a point where we had become strong enough as a community that we thought we could begin to sustain non-essential projects. At the time, we used an analogy, not a very flattering one, but one that was helpful to us. We compared ourselves to a baby. When the baby is young and in the crib, its arms and legs are pretty useless. As it grows, it begins to use its limbs, for example, to climb out of the crib. In other words, we saw that our “arms and legs” were developing and that they were given to us to accomplish some things as we continued to grow in age, grace and wisdom. That didn’t mean we should stop breathing and eating. We weren’t supposed to stop being who we were, but we felt it was time to begin doing only the works that our Father wanted us to do.

Eventually we came to a clear understanding of what kind of community God wanted us to be and what kind of work he had for us to do. We captured this understanding in a list of goals—originally six and later seven:

- To be a community with branches wherever the Lord wants us to grow

- Influence public opinion and affect prevailing ideas in the church and the world

- Establish movements to evangelize and organize their members to influence secular environments

- To invent useful solutions to the basic problems in the modern world

- To care for the materially poor and for victims of injustice

- To foster the spread of the Baptism of the Holy Spirit

- To educate young people in a true and integral Christian humanism in our schools and seminars.

The first goal, to be a community with branches wherever the Lord wants us to grow, is more important than the others. The words “to be” are important. Our other goals deal with work for us “to do.” If a conflict developed between doing some sort of outreach and being a community, being a community would take priority.

The question then was twofold. One: how could we do what the Lord wanted us to do, without sacrificing His primary call for us to be a community? Two: how could we accomplish His other goals for us effectively, in a way appropriate to them? Returning to the Trinidadian example, one could say we wanted to take care of the family and have good roads. There is, after all, a lot to be said for good roads. The question then became: how could we organize the community to accomplish certain works in a way that both introduced skilled specialization and integrated these works into our branches? In other words we wanted to introduce certain non-essential works into the community, not by deconstructing the community but by embedding these works into the community. In order to achieve all of this we structured the community according to branches and program offices, using a matrix style of organization.

How the Matrix Works in the People of Praise

What we understand by and include under the simple title “People of Praise” is extremely complex. Take for example, all the different kinds of coordinators: branch coordinators (which are area coordinators and division coordinators), mission coordinators (responsible for our small branches), principal branch coordinators, program coordinators and head coordinators (who comprise the Board of Governors), and the overall coordinator. Then there are all the various governing bodies: Board of Governors, branch coordinators’ meeting (principal branch coordinator, plus division coordinators, plus area coordinators), area coordinators’ meeting (principal branch coordinator plus area coordinators), Branch Relations Council, Program Coordinators’ Council, to name a few. This section is a detailed exposition of the way we are organized, especially in regard to how we have structured the interface between our life and work. We have to understand the structure in order to make it work well.

The normal life of the community takes place in the branches. They are the place where we love God and one another and are structured in a way that makes this possible. The principal branch coordinator is the head of a branch. His authority in the branch is analogous to that of the overall coordinator of the whole community. He is responsible for the welfare of the branch and its members; is always “eager to maintain the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace” (Eph. 4:3); and relies on Christ’s gifts “that some should be apostles, some prophets, some evangelists, some pastors and teachers” (Eph. 4:11). The principal branch coordinator is appointed by the overall coordinator, who selects him from a list of three men who were nominated by the branch coordinators. He serves for a fixed term of office and his appointment must be confirmed by the Board of Governors.

The work of the community, those activities we undertake in the pursuit of our goals which do not strictly speaking fall under the category of building up the common life in a branch, are located in various programs run by program coordinators. Our Principles of Structure and Government enumerate five program coordinators: coordinator of publications, of action movements, of education, of Christian life movements and of missions. After consultation with the head coordinators, principal branch coordinators and other program coordinators, the overall coordinator appoints and removes program coordinators. The appointment must be confirmed by the Board of Governors. Program offices are staff organizations which assist the respective program coordinators in the execution of their program responsibilities. Program coordinators (along with their assistants) can and currently do meet together in a Program Coordinators’ Council.

Principal branch coordinators and program coordinators have the same rank and are accountable to the overall coordinator, although he may manage his relations with them via a representative, via the Program Coordinators’ Council and the Branch Relations Council or some combination of these. One place then where the life and work of the community are united is in the office of the overall coordinator, accountable to the Board of Governors which is the highest authority in the community.

Annual coordinator assemblies are another place where the life and work of the community are united. The Budget Assembly, attended by members of the Board of Governors, principal branch coordinators and program coordinators meets for the purpose of discussing the proposed community budget. Although our Principles of Structure and Government do not explicitly state this, two other coordinator’s assemblies, attended by the same people as the Budget Assembly, were originally held concurrently with the Budget Assembly: the Branches Review Assembly which meets for the purpose of annually reviewing the life in the branches of the community and the Program Offices Review Assembly which meets for the purpose of reviewing the goals, objectives and performance of the program offices and the life being lived in the divisions (for divisions see below).

The idea was that besides jointly participating in the budget review, the program coordinators and head coordinators would hear the reports from the branches and participate in the discussions about branch life and the principal branch coordinators and head coordinators would hear the reports from the programs and participate in discussions about the various works of the community. These meetings were meant to be a place where these coordinators had the opportunity to come to one mind and heart about the life and work of the community.

The community is not, however, organized so that the work of the program offices exists alongside branch life, with some people belonging to a program office and others belonging to a branch, with lines of authority running vertically. Rather, program offices mostly get their work done by running various projects that are embedded in the branches. The work is done by people who are located in a branch, but sometimes they may need to be assigned to a non-branch location.

Program offices run projects staffed by members of local branches. A division is established in a branch to perform projects for program offices and to provide a distinctive pattern of life, approved by the Board of Governors, that supports project workers. A division is established by the overall coordinator, in consultation with the appropriate program coordinator and principal branch coordinator. A division coordinator, who is the head of the division, is appointed by the overall coordinator in consultation with the appropriate program coordinator and branch coordinators. Both these acts are subject to confirmation by the Board of Governors.

The division coordinator has the same rank as an area coordinator and is one of the branch coordinators. He joins the area coordinators and principal branch coordinator for a monthly branch coordinators’ meeting, where he and his fellow coordinators come to unity of mind and heart about our life and work. A division coordinator is accountable to the principal branch coordinator on pastoral matters in his division and to his program coordinator for project work.

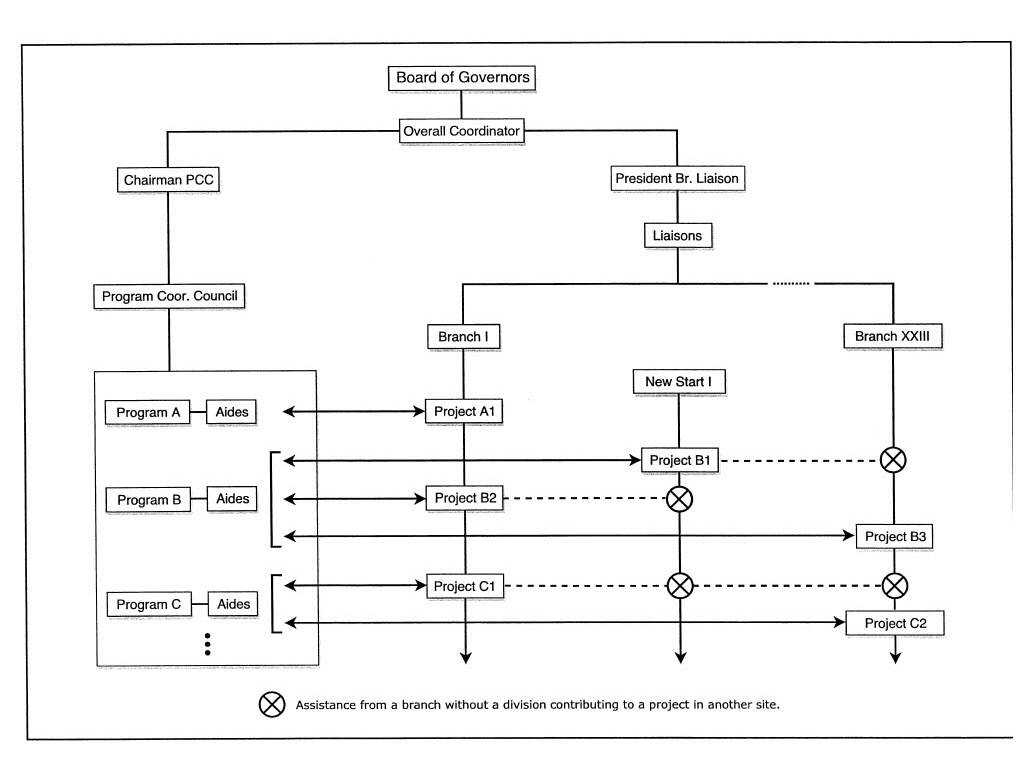

On an organizational diagram the lines of authority run, then, both vertically and horizontally. [See the diagram below.]

The lines on the diagram can be thought of as lines indicating the flow of information and cooperation among all the parts. This way of organizing ourselves is called a matrix management system because the organizational chart with its rows and columns somewhat resembles a matrix. (In mathematics, a matrix is an arrangement of numbers, symbols, or letters in rows and columns which is used in solving mathematical problems.)

Two things are worth noting at this point. First: branch coordinators can initiate the process of establishing a division in their branch. Second: sometimes a branch sets up a project which is not part of one of our programs. In such cases, it would be wise for the branch to organize itself in a way similar to the way the community as a whole is organized so that the “doing” doesn’t destroy the branch, which is first and foremost, a community. That is, if a branch starts a project or projects, it would be wise to use a matrix style of organization, if it can’t handle the projects in a family way (i.e., it is a larger branch) and therefore needs some organization. Again, this way of organizing allows an area to be the place where we love and serve one another and avoids the danger of an area becoming simply a functional organization providing a means to accomplish some projects. After all, we are not a community of projects.

The key players in the matrix are the division coordinators, program coordinators, area coordinators and principal branch coordinators. It will be worthwhile, then, to describe their roles in more detail.

Division Coordinators

The division coordinator’s role is primarily work oriented. He oversees a project (or projects) for his particular Program Office and is responsible for everything directly related to a project. He or his delegate manages the actual work of a project. His interface with the area coordinators and principal branch coordinator involves consultation, negotiation and reporting. He consults with his fellow branch coordinators so that, whenever possible, branch concerns can be addressed. He also wants to benefit from the expertise and experience of his fellow coordinators, when possible. Of course, he takes every opportunity to tap into the special skills of other branch members too. In order to move his work forward he is constantly negotiating and problem-solving with his fellow coordinators. He has to negotiate the use of branch facilities and equipment, coordinate division and branch schedules, obtain help with such things as showers, wedding and funerals, and find, when needed, mutually agreeable ways to tap into the branch’s pastoral resources.2 To accomplish the work of the division he needs the cooperation and support of the other branch coordinators. He also makes every effort to keep his fellow coordinators informed about the progress of the division’s work, so some of his interaction with them involves sharing what’s going on.

Besides interfacing with branch coordinators, a division coordinator also relates to his program coordinator. He is after all overseeing a project for the Program Office. He keeps the program coordinator up to date about the progress of a project, problems the project is encountering, and so on. He also works with the program coordinator in the budgeting process and planning new projects. He benefits from the centralized planning of all the Program Offices and from other divisions’ experience and expertise through his program coordinator. Although the division coordinator is responsible for a project, he does not decide a major issue or policy without the concurrence of his program coordinator.

Program Coordinators

The program coordinator, for his part, doesn’t run the project but he has the responsibility to see that the project contributes to the broader program goals. He does everything he can to ensure the success of the project by making sure the local project sites have the resources they need to get the job done. Besides directing and serving division coordinators, he is also a link between divisions [sic] coordinators themselves and a link between division coordinators and the office of the overall coordinator. In his role, he relates to the overall coordinator or his representative, the head coordinators, other program coordinators and principal branch coordinators reporting to them about the progress of the work. On occasion he also represents the program to rank and file community members, for example, at community meetings. He oversees the initiation of a project, the planning for a project and the yearly budgeting process. He is responsible for monitoring projects, for insuring that they are proceeding according to the original plan and for changing that plan if needed. He handles any problems which arise with regard to a project or to relations with a branch. In short, he needs the capacity to make our complex People of Praise organization serve a project’s needs and, most importantly, he keeps information flowing.

When a division coordinator needs additional personnel for a project, he makes his needs known to his program coordinator. The program coordinator first brings this need to the Program Coordinators’ Council. Sometimes this need can be met by sharing the time and skills of someone between programs or by temporarily loaning someone from one program to another. (Of course, the person directly affected is consulted.) If he needs more personnel, the program coordinator can ask his fellow program coordinators about who they might recommend to do this particular work and he can describe the need to a principal branch coordinator and ask him for a recommendation about who might fill the position. Then the request for a particular person to be assigned to a division goes to the overall coordinator. After consulting with the principal branch coordinator, the overall coordinator assigns the person to a division.

Area Coordinators

In many ways the role of an area coordinator is the most important one in the community. He has pastoral responsibility for members belonging to his area, especially for the elderly, widows, children and weaker members of the body. Along with his area leaders, he supports his brothers and sisters in the “sometimes painful growth toward holiness and deeper relationship with the Lord” (S/P 5) and helps area members navigate the changing circumstances of life with the gospel as their compass (job changes, marriage, children, empty nest, retirement, approaching death). Likewise he does what he can to make sure: 1) that an area member does not fall away when he or she experiences tribulation or persecution on account of the gospel 2) that area members understand the gospel so that the evil one doesn’t snatch the word sown in their hearts and 3) that the cares of the world and the delight in riches don’t choke out the gospel in area members’ lives (Mt. 13:19–22). He is especially mindful that no one can serve two masters, in particular God and Money, and so, humbly, he does everything he can to see to it that he himself and those he is responsible for “use our possessions in obedience to the gospel” (S/P 6).

He shoulders this all important pastoral responsibility which includes first and foremost enabling men’s and women’s groups to function properly. His pastoral responsibility also includes overseeing service in the area, the work of the handmaids, planning area meetings, meeting with area leaders, training and forming area leaders, implementing our pastoral policies, maintaining apostolic fervor in the area, supporting area members who are “bringing excellence to their work as a service to mankind and letting this service be infused with the spirit of the gospel” (S/P14), encouraging the proper exercise of charismatic gifts and so on. Besides all this, he usually is holding down a full time job! Furthermore, on account of his responsibilities, he usually feels the need to pray, read Scripture and study, more not less. He is the linchpin of the community. Areas are, after all, the place where community life has to happen.

Principal Branch Coordinators

The principal branch coordinator is the visible principle of unity in a branch. One of his most important responsibilities is leading the branch coordinators, that is, the area coordinators and the division coordinators, to a high degree of unity of mind and heart in governing the branch. He is constantly fostering a spirit of brotherhood and sisterhood, a spirit of self control and zeal for the work of the Lord, including the work of the divisions, among all members of the branch. He serves the branch coordinators’ needs and indeed all branch members’ needs. He is always looking for ways to equip each member of the branch to bring others to Christ and sees to it that branch members carry out their own responsibilities. He is responsible for accepting and training new community members and for providing suitable formation for all branch members. He represents the branch to the overall coordinator, submitting monthly branch reports to the overall coordinator, attends Branch Review, Program Review and Budget Assemblies, and heads the area coordinators’ meetings and branch coordinators’ meetings.

The principal branch coordinator has a high call to serve as Jesus served. He must use his gift freely and generously, in unity with the other leadership gifts, in whatever ways the Lord may call him to serve his body. He must always keep in mind the instruction of Peter (1 Peter 5:1–4): “Now may I who am myself an elder say word [sic] to you, my fellow elders? I speak as one who actually saw Christ suffer, and as one who will share with you the glories that are to be unfolded to us. I urge you then to see that you [sic] ‘flock of God’ is properly fed and cared for. Accept the responsibility of looking after them willingly and not because you feel you can’t get out of it, doing your work not for what you can make, but because you are really concerned for their well-being. You should aim not at being ‘little tin gods’ but as examples of Christian living in the eyes of the flock committed to your charge. And then, when the chief shepherd reveals himself, you will receive the crown of glory which cannot fade.”

Making It Work

This matrix style of organization and the differentiation of roles concomitant upon it allows the community to take on works that are product-oriented. The programs are organized to produce, for example, a new branch, a movement or a magazine while allowing for mobility, flexibility, functionality, deadlines and both cross-branch and cross-program teamwork. At the same time it allows the branches to be community-oriented and to continue a way of life which fosters growth in holiness and love of one another, provides pastoral care, enables mutual service and is a light to all those we encounter.

It’s no wonder that the matrix style of organization was and is so appealing. It provides a way to take non-essential activities off the plates of the area coordinators and principal branch coordinators, freeing them up to concentrate on the more essential things. It provides a way for us to do what the Lord wants us to do without sacrificing his primary call for us to be a community and, at the same time, to accomplish his other goals for us effectively, in a way appropriate to them.

We have always been a people who know the place and importance of planning. For example, in a 1972 workshop we talked about how to build community.3 We emphasize the importance of having a clear grasp of the goal or purpose, namely to create a people who are united to God; and having a pastoral plan for accomplishing that. Such pastoral planning is no small task. Here is a rough transcription of just one moment in the talk:

. . . determining what your purpose is, setting objectives, finding out what the method is, what exactly in particular you are going to do, what in detail is your plan to accomplish the objectives you have and what kind of system you are going to have to check and see if you accomplished what you set out to accomplish, what kind of mechanism are you going to build into your system to see to it that the plan improves and can be changed . . . . how are you going to verify that you accomplished what you set out to accomplish, what criteria are you going to use to determine that you have been successful and what kind of mechanism do you have built into your system that makes it possible to change your objectives . . .

Being a community doesn’t just happen, we said.

Today, this kind of pastoral planning takes place on the branch level. It is best done locally, because important circumstances each branch faces vary. The planning done in the Program Offices is different, however. It is characterized by centralized planning and control and decentralized project execution. One of the benefits of our structure is that it allows both for local pastoral planning and centralized program planning.

The Program Coordinators’ Council serves as a planning and review board for our work. It reviews proposed projects, sets objectives and actions for the work and monitors ongoing projects. A basic and simple device, called a “Project Approval Document” (PAD) is a principal element in this planning and review work. It includes:

- a broad description of the project

- what it is to accomplish

- how it fits into the Program goals

- how it will be organized and managed

- a schedule

- principle [sic] milestones for measuring progress

- estimated budget

- facilities and personnel required

Since it is often the case that the precise specifications of a project and the exact resource needs are unknown at the outset of planning or implementation, modifications of the PAD are not uncommon.

The Project Approval Document is a written agreement which facilitates careful planning and monitoring. Although ideas for projects can originate from any where in the community, the actual PAD is the responsibility of the program coordinator concerned. Usually the writing of the PAD is the result of a joint venture between the program coordinator and the division coordinator. The Program Coordinators’ Council discusses a new project, and eventually the head of the Program Coordinator’s Council approves the PAD and submits it to the overall coordinator.

Words like “centralized planning,” “monitoring,” “control” and “submit” can aggravate us because we live in such an equalitarian [sic] culture. Nonetheless, centralized planning and control in a situation where related projects are executed in diverse geographical sites are a great advantage. They bring order and promote effectiveness, among other things. It is also an advantage on account of a spiritual principle articulated in a 1974 community meeting: “if you have a chance to get into a headed situation . . . jump at the chance . . . it liberates the power of God.”4 Whether it be on a personal level or on a project/work level, it is just as true today as it was then: entering freely into a headed situation is a key to unlocking God’s power.

The whole planning process, whether it is local pastoral planning or centralized program planning, is a tool. In and of itself, it is not a decision-making process. All the discussion, fact-finding and planning, put those responsible in a position to discern God’s will. And plans discussed and discerned are not a law. God is active also. He opens doors and creates unexpected opportunities. He closes down well-planned and well-discerned projects. As the old adage goes, man proposes, God disposes.

Just as there is, in the community, a tension regarding being and doing there is a tension between local branches and centralized programs. Our structures are locally determined: sections, areas and branches. Leadership is local. For example, it’s not the case that everyone is relating directly to the overall coordinator. In larger branches, the area is meant to be the locus of community life. And the weekly meeting of the community is primary among our commitments. We are not just a community of like-minded individuals. Meeting weekly is necessary to our being a community.

Localism is important because we recognize the importance of subsidiarity. Matters ought to be handled by the smallest, lowest, least centralized authority capable of addressing that matter effectively. For example, financial needs not met in the family are best met in the men’s group. It’s better, more humane, to have our needs met by someone who knows us, someone who is intimately familiar with our situation. Localism makes love substantial, real. A centralized authority should have a subsidiary function performing only those tasks which cannot be performed effectively at a more immediate and local level. For example, if the need is too great for the men’s group, go to the sharing fund.

Program offices perform tasks which cannot be performed effectively at a more immediate and local level. They provide a way for us to pool our resources to increase our effectiveness in achieving our goals. Collaboration among projects located in geographically dispersed sites needs coordination and unification. In order to accomplish our goals—goals that are secondary to being a community, but things that God has called us to do—centralized planning and control with decentralized project execution are preferable to branches working on related projects in relative isolation from one another.

Returning to the Trinidadian example again, it is often ideal to have the construction of an interstate taking place simultaneously in more than one locale. However, a good interstate, one that accomplishes its goal effectively, requires centralized planning even though it might be very beneficial for a particular geographical locale (think branch) to do the planning for their part of the interstate. In our case, building local community is our priority, but the matrix organizational structure allows us to do that and to maximize the achievement of our other goals. We don’t have to abandon good roads.

The tension between local branches and centralized programs which do the work of the community as a whole doesn’t go away. For example, we can strengthen the spirit of a branch when we foster a sense of localism, but too-strong branch identification on the part of individual branch members can make it difficult to accomplish our community-wide goals. These goals sometimes require collaboration from several branches or project sites and the willingness to move to a project site or support a non-local work. However, with wise leadership, the “we” that is so characteristic of community life can apply to both the branch and the community as a whole. We are after all one community in different places, not an alliance of separate communities each doing and being its own thing.

It is already evident that clear and frequent communication is a central feature of our matrix management system. In a branch, division coordinators need to keep other branch coordinators informed about the projects happening in the branch and branch coordinators need to keep the division coordinators informed about how various projects are affecting the branch. Because of so many shared resources, some of this communication will inevitably take the form of problem solving. On a community-wide level, program coordinators and principal branch coordinators have a chance to exchange information at the Branch Review, Program Review and Budget Assemblies and at various leaders’ conferences. As needed, their exchange of information can take place in other mutually agreed-upon ways. Program coordinators are also in frequent contact with their division coordinators and other program coordinators. Of course, the program coordinator keeps the overall coordinator and the Board of Governors informed, either directly or via the head of the Program Coordinator’s Council. Project Approval Documents, where the key elements of a project are specified, are an invaluable aid to communicating what’s going on in the various programs.

In a matrix, program coordinators and their representative division coordinators serve best when they operate by the “principle of no surprises.” That is to say, they are keeping other members of the matrix appraised [sic; “apprised”?] of proposals, new projects, emerging difficulties, etc. Ideally, before a project is implemented or a policy decision is made, affected parties in a branch or branches have a chance to hear about it. The more key participants understand a project and its goals and the more they have a chance to give input before a final decision is made the better the matrix works and the better the projects become.

There are many opportunities for communication and other types of collaboration built into our structure, but ultimately it is the men who fill the roles of program coordinator, division coordinator, principal branch coordinator and area coordinator who make it work. This is no small task because opportunities for conflict abound in every matrix organization, even in organizations that are very different from the People of Praise. Tension between local pastoral planning and centralized program planning and more generally between “being” and “doing” are part of our matrix structure. Furthermore, for the most part the branches and programs have different goals: a natural conflict situation.

Conflicts can be resolved in good order. For example, principal branch coordinators and program coordinators are of equal rank and when there is trouble with something happening in a branch, they should first try to work it out with each other. Failing that they should go to the overall coordinator to reach an agreement. Nonetheless, as our Principles of Structure and Government note, “Special care shall be taken to guard against factions within the government of the community. In coordinators’ assemblies principal branch coordinators are strictly enjoined from prejudicing in any way the authority of the program coordinators and vice versa.”

For our work to be integrated into the life of the community it is axiomatic that the program coordinators are concerned for and supportive of the ongoing life of the branches just as the principal branch coordinators are concerned for and supportive of our program work. At community meetings, coordinators’ meetings, leaders’ conferences and indeed at all times, each should speak well of the other’s work, taking care to foster all the good things we are doing together. “There are varieties of services, but the same Lord; and there are varieties of activities but it is the same God who activates all of them in everyone. To each is given the manifestation of the Spirit for the common good” (1 Cor. 12:5–7).

Footnotes [from original text]

1. Being alive in Christ includes bringing people, both inside and outside of the community, closer to Christ, in whatever way is possible. That is, it includes apostolic activity on the part of individual community members. An organized community-wide or branch-wide apostolic work is another thing.

Return to text

2. Our original vision for divisions was that they would rely on mature community members who needed minimal pastoral care and who could sacrifice some aspects of community life for the sake of the work. However, today that is not always the case. The tension between being and doing runs through every aspect of our life.

Return to text

3. In the file library search “Basic Christian Community Workshop” and then go to the talk entitled “Planning.”

Return to text

4. In the file library search “1974 Authority.”

Return to text

Copyright © 2022 People of Praise, Inc.